Application & Construction

The building material is crucial

Airtightness of buildings: advantages of using AAC

Loading...Why is airtightness in buildings important?

The main purpose of airtightness is the avoidance of uncontrolled leakage/ingress of air between controlled (air-conditioned) environments and non-controlled ones. When designing and then building a highly energy efficient building, it is important to prevent the internal, conditioned air from being dispersed to the outside through cracks or openings in the building’s envelope. That is why we try to create a perfectly airtight building. Airtightness helps prevent the dispersion of the energy contained in the warm or cool air present inside the building.

Airtightness can be achieved by controlling potential leaks in the building, specifically those associated with:

• air piping systems (and around such pipes) which carry fluids from inside the building to the outside,

• electrical piping systems (and around such pipes) which carry cables and wiring from inside the building to the outside,

• doors and windows and their relative seals, both primary and secondary, and

• load-bearing structures, walls and roofs, both horizontal and vertical, by ensuring a continuous, airtight layer especially where this is interrupted by the building’s systems and built-in parts.

The second reason, but no less important, why a building needs to be airtight is to avoid the formation of condensation. It is normal, during both summer and winter, to see “migration” of the water vapour contained in the air. This transfer of humidity changes direction according to the season: from the inside to the outside (mainly in winter) and in the opposite direction in summer (in the presence of air conditioning). This normal migration, especially if left uncontrolled, implies the potential formation of significant amounts of condensation in the transit areas, i.e. inside the building envelope, which is usually made up of several layers. Very often the greatest losses occur through cracks or openings that are found close to load-bearing elements or in the connections of load-bearing elements made from timber. If this migration of vapour is not controlled, there is a risk that the load-bearing structures will degenerate.

The migration of vapour is a natural phenomenon, regulated by physical and technical laws, which seeks to balance (like communicating vessels) two areas with different levels of humidity. People often think that, in winter, it is better not to open the windows when it is foggy outside. But this is, in fact, wrong since the air outside, being much colder than the air inside, is also always drier (less humid) than the air inside. If we transferred the outside air inside the building, and then heated it to 20°C, we would significantly reduce the relative internal humidity, thus improving the well-being of the people within.

The third reason, precisely relating to the internal conditions of well-being, is the proper operation of the Controlled Mechanical Ventilation (CMV) system, by now an almost obligatory choice for near-zero energy buildings. This system, essential for the well-being of buildings and their users, brings with it a series of related issues that can affect its operation.

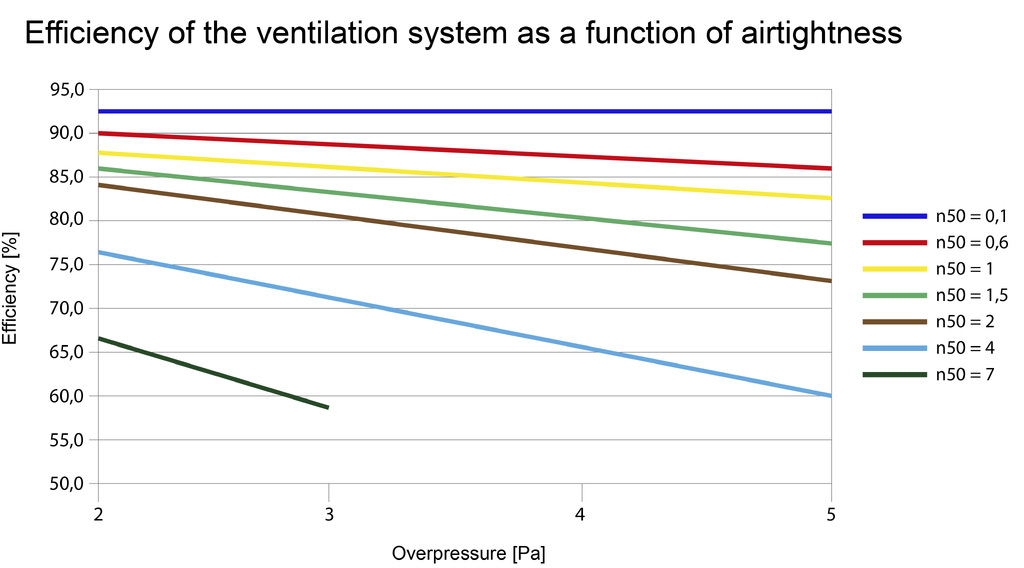

In Figure 1, taken from an article in the magazine published by the “Agenzia Casa Clima Due Gradi”, 2021-1, the change in heat recovery performance is shown as a function of the airtightness of the building as the required overpressure increases. Only excellent, n50, airtightness, indicatively lower than 0.6 h-1, allows significant overpressure levels to be achieved, without negatively affecting performance.

The reason for the formation of condensation

In buildings, as mentioned above, the air inside, full of humidity, tends to migrate outwards to seek a balance. Migration through the building envelope, which is partly reduced with various vapour barriers, leads to vapour being transferred to external layers of the composite system consisting of load bearing structure and insulation. When vapour meets a significant and sudden reduction in temperature, it forms condensation within these layers. The accumulation of a small quantity of condensation is considered normal and even expected and, in any case, the moisture evaporates in summer. But a significant accumulation can potentially damage both the insulating materials and the building’s structure itself. The presence of condensation inside wall cavities can lead to the formation of mould and can create unhealthy environments and potential health problems for the building’s users.

In buildings, as mentioned above, the air inside, full of humidity, tends to migrate outwards to seek a balance. Migration through the building envelope, which is partly reduced with various vapour barriers, leads to vapour being transferred to external layers of the composite system consisting of load bearing structure and insulation. When vapour meets a significant and sudden reduction in temperature, it forms condensation within these layers. The accumulation of a small quantity of condensation is considered normal and even expected and, in any case, the moisture evaporates in summer. But a significant accumulation can potentially damage both the insulating materials and the building’s structure itself. The presence of condensation inside wall cavities can lead to the formation of mould and can create unhealthy environments and potential health problems for the building’s users.

One might think that, in some cases, the best solution is simply to construct buildings with lots of openings, in such a way that the internal air is constantly being exchanged with air from the outside which, in winter, is always less humid. The fact that this migration can occur without control, through cracks, worsens the situation and, as already mentioned, can seriously damage the building’s structure. The goal, therefore, is the opposite: to build buildings that are “airtight but permeable”, by avoiding the presence of openings and creating, in the case of new buildings, a highly vapour permeable building envelope with progressively lower resistance to the passage of vapour from the inside to the outside in order to avoid condensation inside the envelope.

How can condensation inside the building envelope be avoided?

• Create a perfectly airtight envelope which will last over time.

• Use a continuous air exchange system with heat recovery, typically a Controlled Mechanical Ventilation (CMV) system.

• Construct the building with single-layer dispersing surfaces which are not subject to interstitial condensation inside the building envelope.

How airtightness can be verified

To verify the airtightness of a building, an international system is used. Specifically, UNI EN ISO 9972:2015 (which replaces the previous UNI EN 13829:2002) provides information on how to verify the airtightness of a building through a test done at the construction site which is called the Blower Door Test (BDT). This standard defines, within the scope of the building’s thermal performance, how to determine air permeability - “Pressurisation method by fan” (the so-called Blower Door Test). The test is done for a variety of reasons and in particular to:

• provide an energy certification for a building,

• provide an energy diagnosis of a building,

• verify the correct installation and use of doors and windows, roofs, walls, and systems to seal the building from air and wind.

The test consists of mechanically creating (through a very large fan positioned inside a metal frame connected with a sealing sheet) a pressure difference, positive or negative, between the inner and the outer part of the building envelope by the introduction of air to, or the extraction of air from the building. Measurements are taken of the air flow required to ensure this pressure difference.

The finished building test (in the case leading to a certification) must be carried out in “USE”, i.e., under the building’s normal conditions of use. Tests can also be done during the construction phase in order to verify, step-by-step, the proper creation of various elements of the air seal.

The test is done by placing a machine for the Blower Door Test on a door or a French window (hence the name “Door Test”). Two tests are then carried out: one under negative pressure and the other at positive pressure. Measurements are taken at different pressures at regular intervals of 10 Pa, starting from 70 Pa down to 30 Pa. The result of the building’s airtightness is a weighted average of the two tests and is defined with a final test value, n50. Essentially, when a building is given an n50 value of 1.0h-1, it means that, in one hour at a pressure of 50 Pa, the building’s volume of air is completely exchanged.

Requirements regarding airtightness under the main Italian and European certification systems

The first Blower Door Test was done in Sweden in 1977. In the same way, the various certification systems that deal directly with the efficiency of a building have long since identified minimum values according to their own certification system, as listed below.

Minergie (Switzerland)

Minergie (RiLuMi - Airtightness measurement (BlowerDoor) for Minergie-P/-A. Mandatory requirements for new buildings ≤ 1.2 Minergie (m3/h∙m2), ≤ 0.8 Minergie A and P (m3/h∙m2).

Thermal regulation (France)

The 2012 thermal regulation requires justification of the air permeability value of individual homes. The air permeability value of Q4Pa-surf must be less than or equal to 0.6 (m3/h∙m2).

Building regulation (Denmark)

The 2018 building regulation requires that air exchange does not exceed 1.0 litre per second by square metre of heated floor when a pressure test is carried out at 50 Pa.

EnEV (Germany)

With the introduction of the EnEV in 2001, in Germany, too, it became standard to test the airtightness of buildings. Since 2020, this has been regulated by the law for building energy (GEG) according to DIN EN ISO 9972.

Passivhaus (Germany, with offices also in Italy)

Single classification class that requires an airtightness of ≤ 0.6 (m3/h∙m2).

CasaClima (autonomous province of Bolzano)

For new buildings, based on their energy class, since 2017 it has been mandatory to verify airtightness: mandatory limits by Class A and B ≤ 1.5 (m3/h∙m2), and for Class GOLD ≤ 0.6 (m3/h∙m2).

Where and how to achieve airtightness in a building and the related issues

The airtightness layer of a building varies between buildings and between various construction systems. The key building elements that are considered essential for ensuring airtightness are analysed below.

Care to be taken for the airtightness of horizontal and inclined walls and surfaces

The perimeter walls of a building completed with AAC blocks are not subject to any particular issues, since the blocks are solid and, therefore, not permeable to air (not to be confused with vapour permeability). These construction systems are installed with thin “continuous” layers of adhesive just 1-2 millimetres thick. The only attention is to be paid to the vertical joints which are not sealed when installing the infill blocks, normally with a vertical tongue-and-groove joint profile. To overcome this potential issue, however, it is sufficient to point the joints superficially or to add, in any case, adhesive to the vertical faces, even on profiled surfaces.

The lack of plaster in the hidden, unplastered areas (between the floor slab and the floor) is of little importance since the air that penetrates through the perimeter cracks of the flooring does not have a significant impact because, as mentioned above, the structures or infill in AAC are made with solid brick, which is not permeable to the air, and are glued with a thin, “continuous” layer of specific mortar a few millimetres thick. The sealing, which is carried out with a levelling compound, or the simple pointing of the vertical joints, in the case of blocks with tongue-and-groove joints, installed under the floor, is, in any case, recommended even if not strictly necessary.

In installing the building’s systems, paying particular attention is not necessary since the chases for these systems are done with extreme precision, with a support behind them which is always solid and free of any significant cavities.

Examples of buildings made with AAC, certified to CasaClima A

We now give two examples of buildings which have been certified, or which are in the process of being certified, to CasaClima Class A. As mentioned earlier, CasaClima buildings must pass the airtightness test in order to obtain certification. For CasaClima A certification, a Blower Door Test value of n50 ≤ 1.5 (m3/h∙m2) is required. We specifically analyse two buildings whose load-bearing structures are in reinforced concrete (pillars/beams) and infill walls constructed with AAC.

CASA G in Selvazzano Dentro

The CASA G in Selvazzano Dentro (PD) building is constructed with the following building envelope layer structure:

Grade level:

- Insulation under foundation in cellular glass granules of 40 cm.

- Foundation in reinforced concrete of 35 cm.

- Insulation above foundation with 8 cm of XPS.

External walls:

- Internal plaster of 2.5 cm (thickness necessary to house the radiant wall heating coils).

- Single-layer infill walls in blocks of AAC of 50 cm.

- External covering of pillars and stringcourses with hollow tiles of AAC of 8 cm and 5 cm

inside over 7 cm of PIR (placed between the pillar and the external hollow tile).

- External render, 1.5 cm.

Ventilated inclined roof:

- Double board in timber, 2.5+2.5 cm.

- Vapour barrier.

- Double layer of wood fibre of 140 kg/m3, 14+14 cm.

- Layer of wood fibre of 260 kg/m3, 2.5 cm.

Windproof flat roof:

- Internal plaster, 2.5 cm.

- Floor slab cement and masonry of 25 cm.

- Bituminous sheath.

- Sloping cement screed, average thickness 8 cm.

- Double layer of polyurethane, 8+8 cm.

- Bituminous sheath.

Systems:

- Air/air heat pump.

- Radiant wall or ceiling under plaster for hot and cold.

- 6 kWp photovoltaic.

- Active dehumidifiers.

- Controlled Mechanical Ventilation.

CASA S in Vicenza (VI)

CASA S in Vicenza is built with the following building envelope layer structure:

Grade level:

- Insulation under foundation in cellular glass granules of 30 cm.

- Foundation in reinforced concrete of 40 cm.

External walls:

- Internal plaster, 1.5 cm.

- Single-layer infill walls in AAC blocks of 48 cm.

- External covering of pillars and stringcourses with mineral insulating panels of 18 cm and 5 cm of AAC hollow tiles on the inside.

- External render, 1.5 cm.

Flat roof:

- Internal plaster, 2.5 cm.

Base in reinforced concrete of 22 cm:

- Sloping cement screed, average thickness 6 cm.

- Bituminous sheath.

- Double layer of PIR, 8+8 cm.

- Bituminous sheath.

Ventilated inclined roof:

- Perforated masonry, 8 cm.

- Base in reinforced concrete of 8 cm.

- Vapour barrier.

- Triple layer of rock wool, 140 kg/m3, 6+10+10 cm.

- Windproof.

Systems:

- Air/air heat pump.

- Radiant ceiling under plaster for hot and cold.

- 6 kWp photovoltaic.

- Active dehumidifiers.

- Controlled Mechanical Ventilation.

Airtightness check of the two buildings

CASA G

The BDT airtightness test did not find any particular issues. The test concluded with an n50 result of 0.15 1/h, which is significantly lower than the minimum required for the building class and a fifth of that required for GOLD class certified buildings. The building was certified CasaClima Class A at 14 kWh/m2a and 2 kg of CO2/m2a.

CASA S

Again, in this case, the BDT airtightness test did not find any particular issues. The test concluded with an n50 result of 0.46 1/h, which again is significantly lower than the minimum required for the building class and a quarter less than that required for GOLD class certified buildings. The building is in the stage of

obtaining a final certification with the goal of being certified CasaClima Class A at 24 kWh/m2a and 3 kg of CO2/m2a.

Final considerations

In analysing the above, the following considerations can be drawn for single-layer AAC structures:

• They have no issues of interstitial condensation.

• They require very little attention in order to achieve excellent airtightness.

• They have the advantage of being installed by the company and have only one process to be checked (in addition to the internal plaster and external render).

• A good part of the possible thermal bridges is resolved with the material itself (doorframes, lintels, windowsills) which, thanks to its isotropic behaviour, guarantees that the complex details, which are to be created with other construction systems, are easily achieved. Just think of making an opening for the window without the now inevitable monoblocs, which simplify the work around the architectural openings, but which are also very expensive. With the material itself, they easily solve the doorframe openings, as well as the insulation under the windowsills. Furthermore, thanks to the isotropic characteristic of AAC, it can be installed in any direction and, therefore, results in very little wasted material.

Conclusions

A building full of air exchange to the external environment increases the heat losses compared to those envisaged in the design and, as has been verified in some cases, the system may not be able to maintain the internal design temperature (especially in the case of strong winds) or, in any case, the heating costs will be higher and the pollution greater. This is not to mention the lack of internal comfort due to air movements, which can be extremely annoying from a thermal point of view but also in terms of acoustics and odours. In fact, wherever air passes, noise and odour pass too.

It can be seen that, in buildings made with AAC, it is much easier to guarantee airtightness and to make the envelope airtight. AAC simplifies construction site problems and allows BDT results to be obtained which are decidedly lower than those of the various mandatory and voluntary certification systems.

The full version of this study can be found under the following link:

https://www.aac-worldwide.com/pdfs

Study Supporter:

((Hier bitte zusätzlich einen QR-Code fürs Heft))